Bacteriophages (viruses that specifically infect bacteria) are important mediators of human health. The approach termed phage therapy involves the use of phages to therapeutically to kill antibiotic resistant bacteria and thereby treat resistant, life-threatening infections. These phage-based approaches are also appealing in applications such as “microbiome sparing” therapies for infections, which means the specific infectious bacterium is killed by the phage and the overall community is impacted less than by an antibiotic treatment. For these reasons, it is important for us as a field to understand how phages infect their hosts, and how bacteria evade phage infections. A recently published manuscript by Sarah Kronheim et al addresses our knowledge gap of how bacteria combat phage infections by outlining a previously understudied chemical-based bacterial defense mechanism against phages.

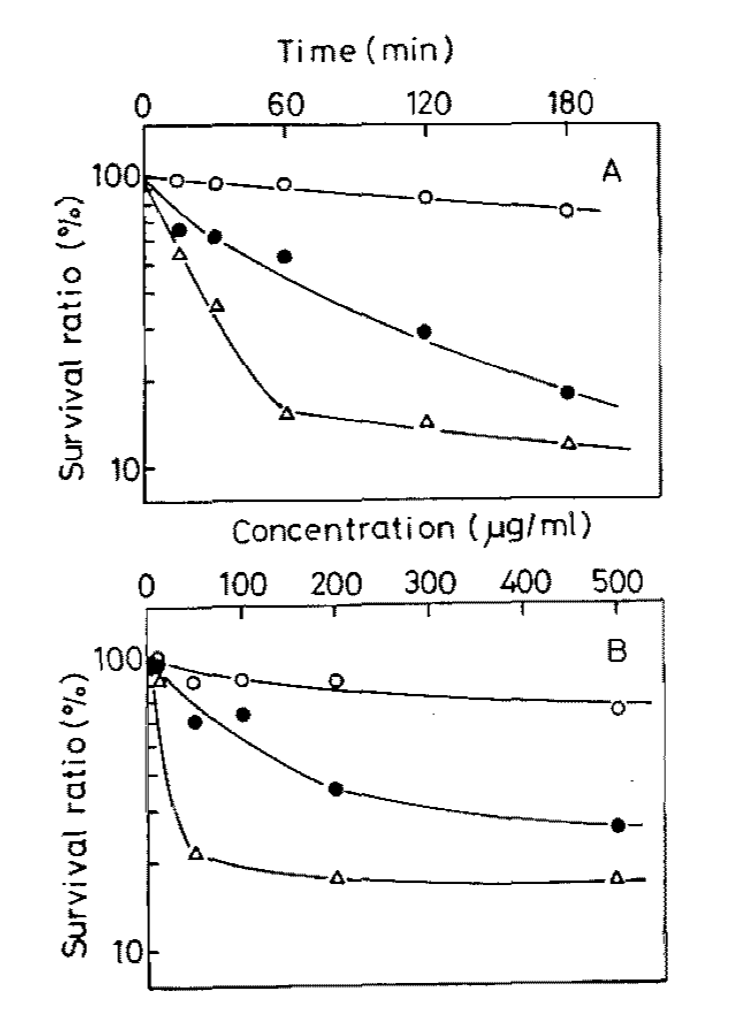

The work of Kronheim et al began with an observation in the scientific literature from decades in the past (here is a link to one of them). That past work noted that bacteriophages were inactivated by bacterial secondary metabolites, which were otherwise of medical interest because of their anti-tumor and antibiotic properties. Although the past groups published their findings, they did not follow up with their work and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the small molecule mediated phage defense mechanisms. Kronheim et al picked up where the past groups left off, and provided a more comprehensive understanding of those understudied mechanisms.

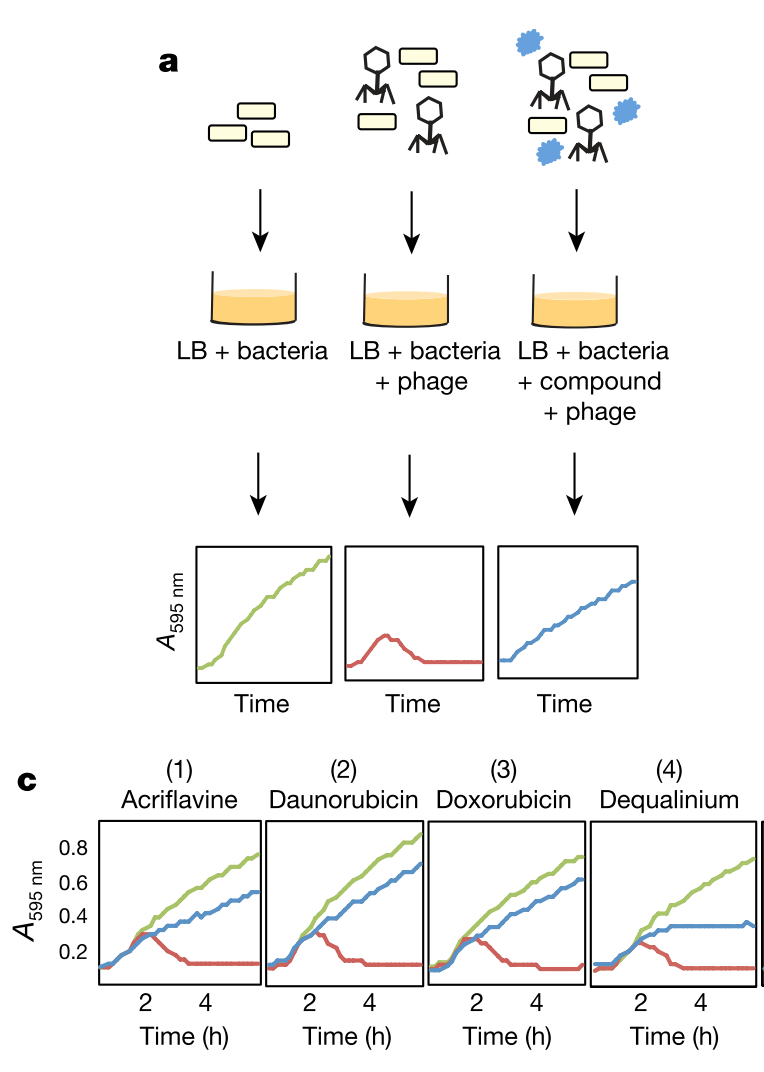

The Kronheim group began their study by performing a small molecule screen to identify which compounds inhibited phage infection of bacteria (the small molecules were largely products of biosynthetic gene clusters, and some represented FDA approved drugs and bioactive molecules). The approach is illustrated in the figure below, which is from the original publication. The screen was successful and the group identified a subset of small molecules that prevented phage infection of their bacterial host (E. coli). In addition to their lab strains, the group confirmed that their observation could be reproduced with phages isolated from nature. They also confirmed that the small molecule inhibitors were produced by the bacteria by testing their media. Together this supports the relevance of their observation, and suggests that the small molecules are biologically relevant outside of the lab system and are actually produced by bacteria.

To understand the mechanism by which the small molecules were operating, the group characterized the molecule functionality and identified them as intercalating agents. They further found that one of the molecules, daunorubicin, acted early in the infectious process, likely after injection of phage DNA into the bacterial cell, but before replication of that DNA. As was reported in the previously existing literature, this was specific for dsDNA phages, although it was observed across diverse phage families. Further work will be required to more completely characterize the underlying mechsnisms of this system.

Overall this study is broadly applicable and we could imagine myriad directions and implications for the work. I am particularly interested in the implications this work will have for human microbiome studies, including both bacterial and viral communities. I wonder whether small molecule drugs or drug candidates having an impact on the microbiome through this mechanism of bacteriophage infection inhibition? I also wonder what implications this could have in our understanding of antibiotic resistance with different antibiotic drugs. Perhaps some antibiotics are more adept to inhibiting bacteriophage infections, and thereby further limit the potential for spread of antibiotic resistance genes through transduction (both generalized and specialized). And how are these metabolites linked to altered viromes, which are themselves associated with disease? There is a lot of opportunity for impactful and interesting future work from this study.

This paper was short, clear, and overall well written so I suggest you check it out (find it here). The link should be open access, and was very kindly provided by the authors for sharing. I also recommend checking out the older paper that I linked above in the second paragraph, because it is interesting to get a baseline historical perspective on this most current work. Finally if I missed something, got it wrong, or if you have some other cool ideas, let me know in the comments, Twitter, email, or telegraph. I always love hearing from you and really appreciate any additional feedback or insights.

comments powered by Disqus