Wow, it’s been about six months since my last post and a lot has been happening! Between pushing through some papers and working on exciting projects in my new job in pharma, it’s been a busy summer. Unfortunately the blogging took a back seat but I’m excited to hop back onto the computer and hopefully keep the posts more frequent moving forward. So let’s dive in!

One of the exciting aspects of human microbiome research has been the continued improvment of functional analysis of the communities through techniques such as metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. One approach to understanding microbiome functionality, which has recently been gaining more traction in the field, has been bacterial biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). This focus was especially apparent at recent microbiome/microbiology conferences, including the Beneficial Microbes conference and ASM Microbe conference.

BGCs are co-localized gene clusters within bacterial genomes that together encode the machinery necessary for synthesis of secondary metabolites. These metabolites have been widely used as natural product drugs and represent an important area in which the microbiome could be impacting its host. Additionally, bioinformatics techniques have been continuously developed to identify these signature clusters, and those techniques are starting to be utilized with microbiome datasets.

Although we can use bioinformatics tools to identify BGCs within bacterial genomes, there are still many challenges in the field. One of these major challenges is that a majority of BGCs remain orphans, which means they have yet to be linked to their secondary metabolite products. A recent paper by Amos et al, published in PNAS and titled Comparative Transcriptomics as a Guide to Natural Product Discovery and Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Functionality, used transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches to provide important insights into orphan BGCs. This week will review some of the highlights from this study and briefly discuss the impact on the human microbiome field.

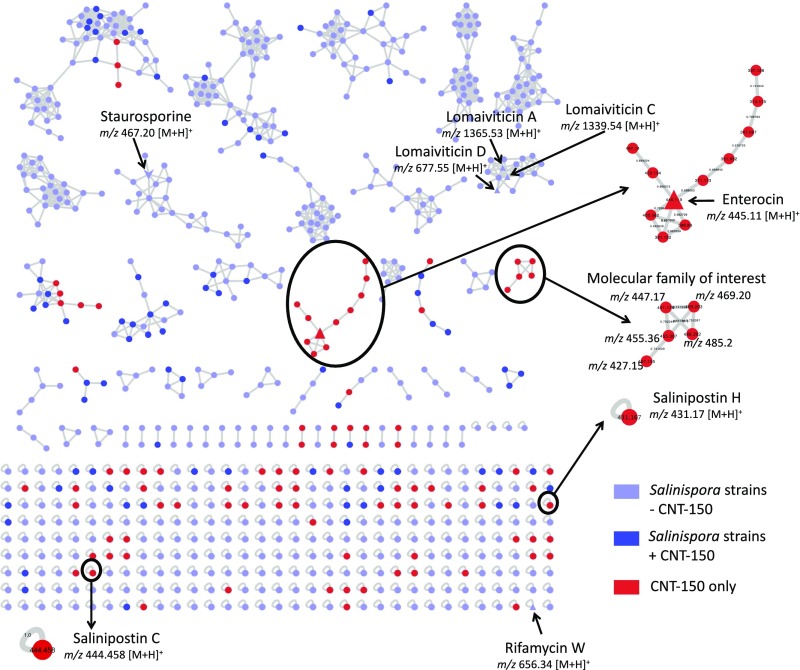

The core of the paper focused on four strains of the bacterium actinomycete Salinospora, marine bacteria which contain high numbers of BGCs. The group started by addressing the question of whether orphan BGC products are undetectable due to transcriptional silence (inactivity) in the laboratory. By performing global transcriptomic analyses (identification of which BGCs are active at the RNA expression level) and pairing it with metabolomic analysis (identification of metabolites, including BGC-produced secondary metabolites) at both stationary and growth phases, the group revealed an interesting phenomenon. While many BGCs were active at the gene transcript level (and therefore not silent), the BGC products (secondary metabolites) were still not readily identifiable. Although some orphan BGCs are the result of transcriptional inactivity (gene silence), this result highlights the important limitations of the other detection techniques such as LC/MS techniques, and the importance of understanding the transcriptional activity of the system being studied.

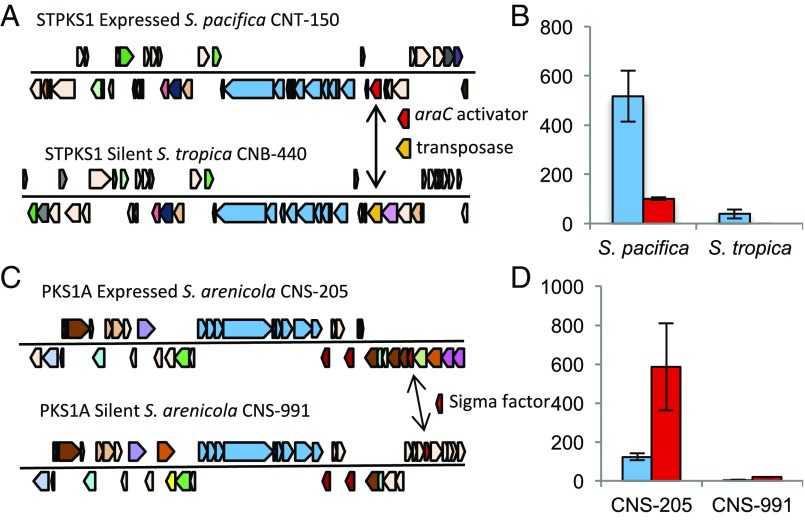

The group followed up on this finding by investigating why some BGCs were differentially expressed between the bacterial strains. In other words, why was the same BGC transcriptionally active in one strain and not another highly similar strain? In one notable example, the group found that one orphan BGC was expressed when it included an activator (araC) upstream of the core BGC operon, and was silent when the activator was replaced with a different gene. This is an especially important result because it highlights our potential ability to use additional genes, such as upstream transcriptional activators, to predict which highly similar BGCs will be expressed in related bacterial genomes. This would be a valuable bioinformatics tool for informing the study of the human microbiome, as well as natural product drug discovery.

Overall this is a very interesting paper with a lot of insights into BGC activity and regulation. But why is this important from a human microbiome perspective? As a lot of groups in the field have already identified, BGC identification techniques from metagenomic datasets of the human microbiome offer an opportunity to identify largely unrecognized functional potential of the communities. The approach also offers implications for natural product discovery from such microbiome datasets. This paper further highlights the importance of integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses into such studies, so that a more accurate observation of the community activity can be achieved.

comments powered by Disqus