It’s no secret that the human microbiome (the collection of bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc that inhabit the human body) has provided unprecedented insights into human health and disease. By beginning to understand the complementary roles that these microbial communities play in parallel with our human body, we are seeing many diseases with new perspectives. These new perspectives are already beginning to inform promising new therapies for truly terrible diseases (i.e. Clostridium difficile infections). Although the microbiome consists of fungi, viruses, archaea, and other microbes, bacteria are by and large the most studied component of the human microbiome. The human virome (the viral component of the human microbiome) is understudied, but especially interesting because it consists primarily of bacteriophages (bacterial viruses), which are capable of modulating bacterial metabolism, function, and community composition.

Many human anatomical site viromes have begun to be studied (gut, mouth, skin, lung). To date, the virome of the urinary bladder, another medically important body site, remains understudied. To address this large knowledge gap, a research group led by Taylor Miller-Ensminger et al, in the lab of Catherine Putonti at Loyola University, recently published a unique characterization of the human urinary virome using culturing and sequencing techniques.

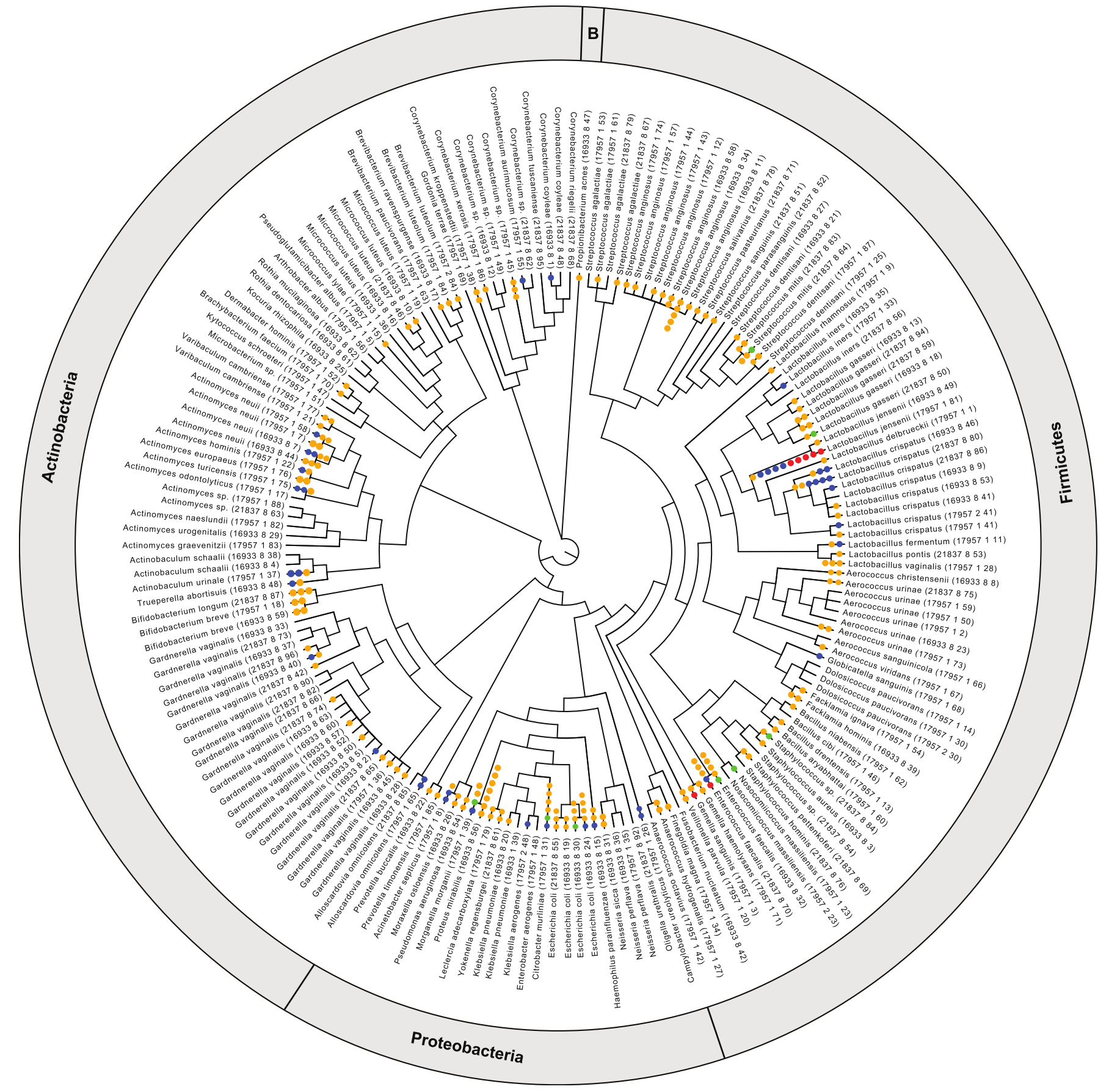

As the authors pointed out in their manuscript, previous studies have detected viruses in urine microbiome using shotgun metagenomic techniques (a standard microbiome characterization approach). What makes this work of Miller-Ensminger et al unique and valuable is that they focus on identifying the prophages (those phages whose genomes are integrated into bacterial genomes) of the urine microbiome. This is valuable because it provides more information about the types of phages present in the urinary tract, and also gives information on what bacteria are likely to be infected by phages. The group accomplished this by culturing/isolating bacteria out of a human cohort and sequencing the isolate genomes. And in case you were thinking about contamination, they used isolated from mid-stream urine collections, as well as aseptically collected with a transurethral catheter.

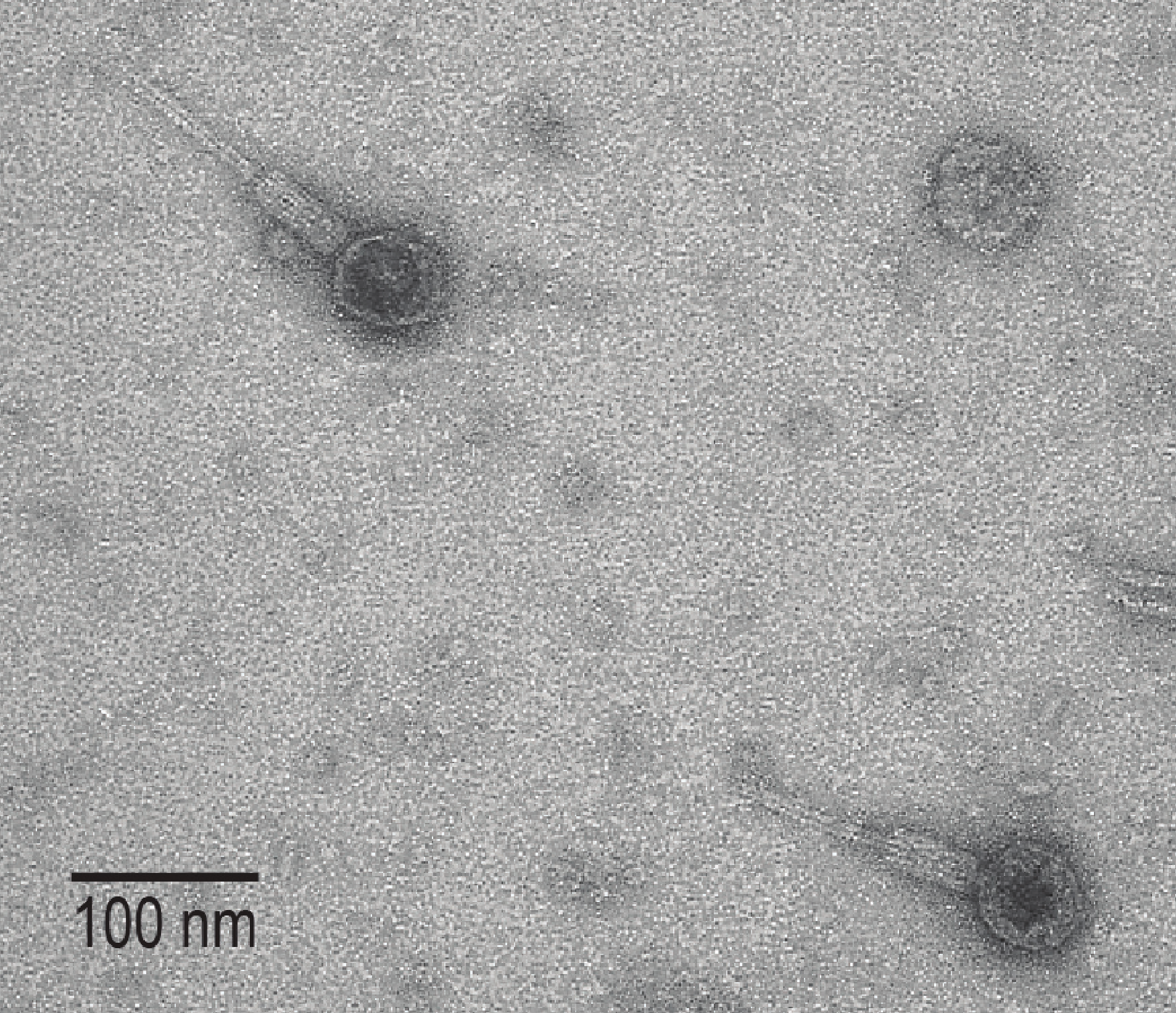

The group ended up with 181 genome assemblies from their collection of isolates, and they identified 226 high confidence phages integrated into those genomes. They were also able to isolate one of their phages out of their samples (see image above). In the end the group added a valuable survey of the lysogenic phages of human urine, and a reference of phages that are linked to their hosts. As the authors mention, this work is especially exciting because it will provide valuable reference material for future studies of the urine microbiome.

One interesting next step that I could envision would be to use the isolate prophage genome sequences with the previous urine metagenomic studies, or perform shotgun sequencing on the samples. It would be interesting to look at the ubiquity of those phages in other sample sets by aligning shotgun metagenomic reads to the prophage sequences. It would also be cool to use a similar approach to start understanding how many of those phages are actively replicating (or maybe only active in disease states). There are a lot of interesting directions for this work and I am excited to see the next study from the group.

Overall this is a very nice paper that is easy to follow, so I suggest checking it out. Their data is also published, so it might be worth integrating the sequences into your own future studies. And of course, please leave me a comment below if you have any questions, comments, or concerns. I always love hearing from readers.

comments powered by Disqus