Introduction

Looking back at this blog, it’s been a YEAR since my last post?! And it’s been an eventful year, both personally and globally. But today I’m excited to discuss a different kind of virus than what we usually here about these days. The virus for discussion today is the bacteriophage, which is a type of virus that only infects and kills bacteria, and not humans or other animals. Here we will focus on some exciting recent work by Fluckiger et al, which implicated a specific bacterial virus as a facilitator of cancer treatment efficacy and immunity. In this post, we will first review the findings of paper, and then speculate on some potential follow up work and the implications of the findings.

In the past couple of years, the microbiome has been implicated as a potentially important factor in cancer treatment and immunity, especially in immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy (ICI). This has included work from Routy et al, Tanoue et al, and others. What is particularly interesting in these papers is that they don’t always agree on the specific microbiome factors impacting ICI response. Some papers suggest one species is important, and another implicates another species or group of species. While this could suggest a need for more uniform analysis across the studies, it could also suggest there is another underlying commonality, or otherwise missing feature, that implicates the microbiome in ICI response.

Linking Phages To Cancer Immunity

The group of Fluckiger et al began their work with an interesting observation. In their model for cancer treatment (in this case it’s chemotherapy, not ICI), they found that the presence of some E. hirae bacterial strains resulted in more effective chemotherapy compared to other bacterial strains. They asked what the underlying mechanism could be to explain such variability between strains. To answer this, they performed a series of targeted follow up experiments and identified a bacteriophage tape measure protein (TMP1 to be exact), which was integrated in the E. hirae genome.

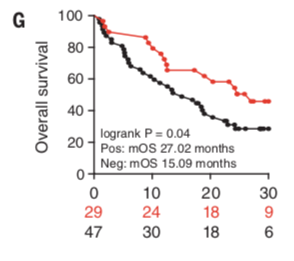

Manuscript figure that shows the TMP1 phage signal may be associated with improved cancer ICI outcome. While this is interesting, more work will be required to determine whether this is actually clinically relevant.

Now this is an interesting finding. Some bacterial strains were effective at improving chemotherapy efficacy because of a bacteriophage infection, and not the bacterium itself. In this case, the TMP1 is a common gene used by bacteriophages in their tail construction process. Both capsids (the heads) and tails of bacteriophages can cause an immune response, and the authors actually found that the improved chemotherapy efficacy was associated with cytotoxic T cell activity (immune cells that kill dangerous cells).

All of this work suggested that the phages were improving an immune response against cancer cells, and the authors hypothesized that it was due to molecular mimicry. Molecular mimicry occurs when microbial or other foreign antigens are similar to a host (e.g. human) protein and cause the immune system to mount a response to itself. As expected, the authors ran a DNA alignment analysis and found that the TMP1 immunogenic region was similar to PSMB4, and mammalian gene that is over-expressed in many cancer cells. After additional work, the authors confirmed that the bacteriophages are improving chemotherapy response by “mimicking” genes found in the cancer cells, and activating the immune system to attack and kill the cancer cells more effectively.

After all of these results, it’s hard to not wonder whether this response holds true for ICI, and not just chemotherapy. The authors of this work did not dive into this question in detail, but they did end the paper by showing that in a single clinical cohort, the presence of the TMP phage was associated with improved ICI therapeutic outcome (see figure above). In other words, it appeared that patients with the TMP phage survived longer than patients without the phage. While this is interesting and encouraging, extensive additional work will be needed to tease this out and understand the clinical implications.

Possible Future Directions

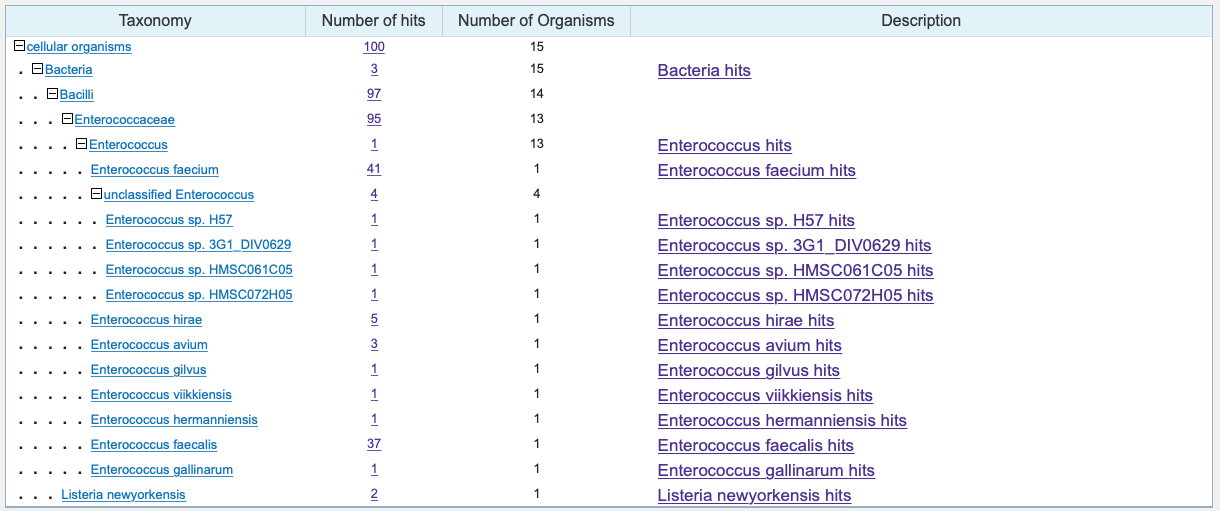

One of the exciting aspects of this paper is thinking about the directions this can go in next. One question I asked as I read this paper was whether this bacteriophage sequence can be found in other bacteria. The authors show us that the phage sequence is found in E. gallinarum, but are there others? I actually went back and performed a BLAST DNA alignment with the TMP1 antigenic sequence TSLARFANI to see what other bacteria contained the sequence. The alignment showed that the bacteriophage sequence is actually found in many different Enterococcus bacteria. It also appeared in a Listeria bacterium.

Results of a simple BLAST DNA alignment to bacteria using the TSLARFANI sequence.

Additionally, it will be interesting to see whether this and other groups follow up on understanding the association of TMP1 with ICI. Perhaps there is a unifying TMP1 signal across previous studies, which wouldn’t be apparent given the analyses done to date. It also begs the question of how antibiotics are associated with the microbiome and cancer treatment efficacy. We know that antibiotics might be associated with ICI efficacy, and they are also associated with bacteriophage activity. This begs the question of whether the two are connected. Finally, it will be interesting to see follow up work to evaluate whether the described signals could be used as therapeutic biomarkers.

Conclusions

Overall this was a really cool study, and it has a lot of results to sift through. I definitely recommend checking it out for more details. It is also going to be incredibly exciting to watch how researchers follow up on this work. This work opens up many more questions of how the microbiome impacts cancer therapy and the immune system.

Did I miss anything, or do you have questions, comments, or concerns? Drop a message in the comments below and let’s get the conversation going.

comments powered by Disqus